It was 1992; my parents were 2 kids in their early twenties who found themselves and each other in the Philippines. They were in Palawan, waiting to be processed at a Vietnamese refugee camp. Though life was uncertain, and my parents didn’t have much, it was some consolation that no one else had much either except for the shared hope they could start anew in the United States.

For my parents, that hope took on a sense of fragility and desperation, because I was growing in my mom’s belly. And that’s how you feel when you want something so hard your heart could break. In the quiet moments between rationed meals, odd jobs, and what felt like stolen moments of happiness, they dreamt of an abundant life where opportunity fell like ripe oranges from branches laden with fruit. A life where every new day basked in an equitable sunlight, the kind that shone the same on everyone regardless of where you came from.

Despite my parents’ circumstances, the hope and joy of bringing new life into the world is universal. The desire to be better for your children transcends cultures and generations, and it gives people the courage to ask for more from themselves and from life. In the Philippines, my father learned to develop film and he made a bit of money from taking pictures of refugees that had just reached the island. How valuable the 4×6 sepia-toned memories must have been, for those skinny smiling people to part with what little they had. My mother recounted a tender moment where my dad had saved enough from his odd job, and she said to him “all I want in this world is a bowl of Pho! If only we could have that taste of home,” she said to him. That night my mom recalled that my father wasn’t very hungry, so she and I shared two bowls of the fragrant noodle soup adorned with a few scant slices of beef that were almost too decadent to eat. When my mother told me she can still smell those bowls 9000 miles away and 32 years later, I realized that even in poverty, love can make you feel infinitely rich.

When it came time for my parents to leave for the United States, they were terrified my mother wouldn’t be allowed to fly because she was seven months pregnant. But her slight frame and baggy clothes concealed me well, and we made it to 1701 Park Road NW—our first home in America. Thanks to an NGO, we were housed in a one-bedroom apartment shared among four families and seven people. Our haven was a full-sized bed, made private by thrifted bedsheets craftily secured to the ceiling with thumbtacks.

Weeks later, at her first ultrasound, my mother learned I was healthy and that she would be having a daughter. My parents were excited by the prospect of a little girl and decided that my mother would be the one to name me. The weeks moved quickly as my parents became acquainted with their new lives in D.C. I asked my mother how she felt in the last month of her pregnancy, and she proudly exclaimed “Mẹ khỏe như trâu” which translates to: your mother was as strong as an ox.

On the morning of October 2nd, her contractions began. Fortunately, most of the apartment had emptied for the workday, but in the haze of labor, she couldn’t recall whether or not she had an audience. She described the pain to my father as a vice of fire tightening across her abdomen, relentless and cyclical, alternating between bouts of intensity and fleeting moments of rest. She remembers sinking to the floor, clutching another family’s bed frame as if she were back on the dinghy making its way to the Philippines, holding onto the mast for dear life as the tiny vessel rose and fell against the foaming waves.

While she was at sea, my mother recalls that my dad was calm. He wanted to help, but he didn’t know how. He kept her company and every now and then a voice would float out to her like a lifeline. “Was it time to call 911?” My mother resisted. Back in the Philippines, she had heard from experienced women that labor was the most excruciating pain a person could bear. And though she wasn’t sure what that meant, my mother knew she hadn’t reached her limit. Eventually though, she relented and shortly after, my father led an EMT into the room. The EMT barely examined her before scooping her into his arms and rushing into the ambulance, my father clambering onto the back. In their hurry, she left behind her shoes, her underwear, practically everything but the nightdress she had on.

We arrived at George Washington Hospital that Friday afternoon where my mother met an angel. Her name was Hạnh, a Vietnamese-speaking doctor who translated and acted as a calming presence for my parents amidst the chaos. At the hospital my mother said no one instructed when to push so she just never stopped pushing. Ignoring her contractions, the exhaustion, and the toll on her body, my mother pushed so forcefully that within the hour, I was born.

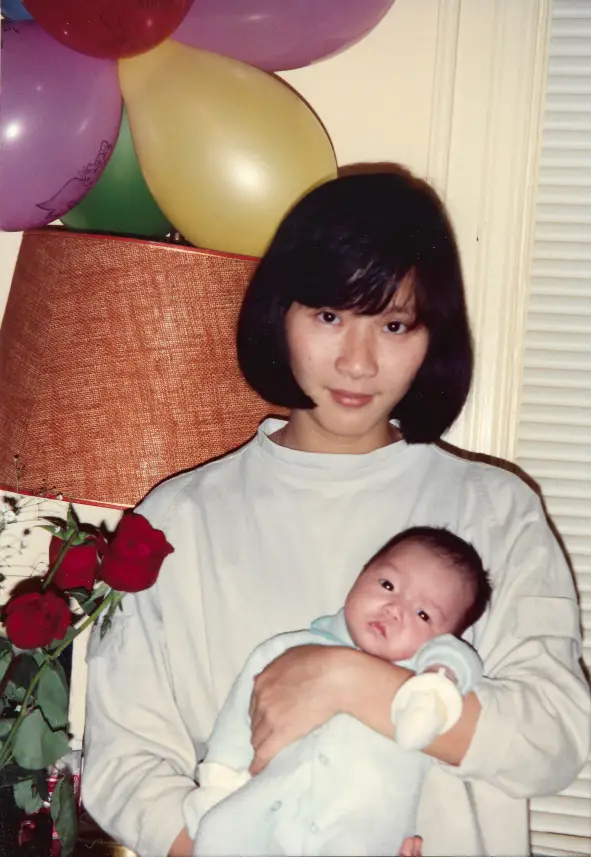

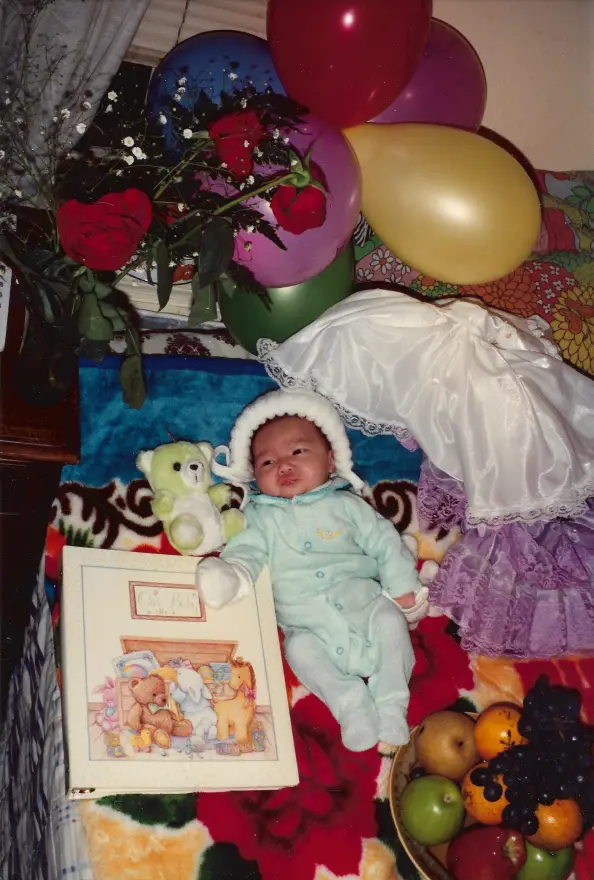

That night, my parents were overjoyed to welcome their first baby into the world. I was small—just 5 pounds—likely due to the limited resources at the refugee camp but otherwise healthy. They named me Khánh Mi, meaning “little bell.” But their celebration was brief because my father had a gig that paid under the table—almost $50 dollars for an entire night of janitorial services. In another world, that amount wouldn’t have been enough to tear him away from his wife and newborn. But my parents were surviving on just $300 a month and every opportunity mattered.

After my father left her side, my mom cradled me in her arms. She recounted to me the loneliness and exhaustion steadily pulling her under. She prayed that someone would come help her so she could sleep. And as she was telling me this story, she smiled—perhaps laughing at the desperation that was now a distant memory. When a nurse finally visited her, she pressed me into the nurse’s arms gesturing for her to take me. They didn’t need words; the nurse had understood. As the nurse whisked me away, I imagine the door closing softly behind her, careful hands turning the knob soundlessly. In the sudden quiet, my mother lay still, the hospital’s fluorescent light seeping in from under the door. Her eyelids fluttered once—maybe twice—before closing. The low hum of machines and gentle beeping became her lullaby, guiding her into a victor’s rest.

Afterword

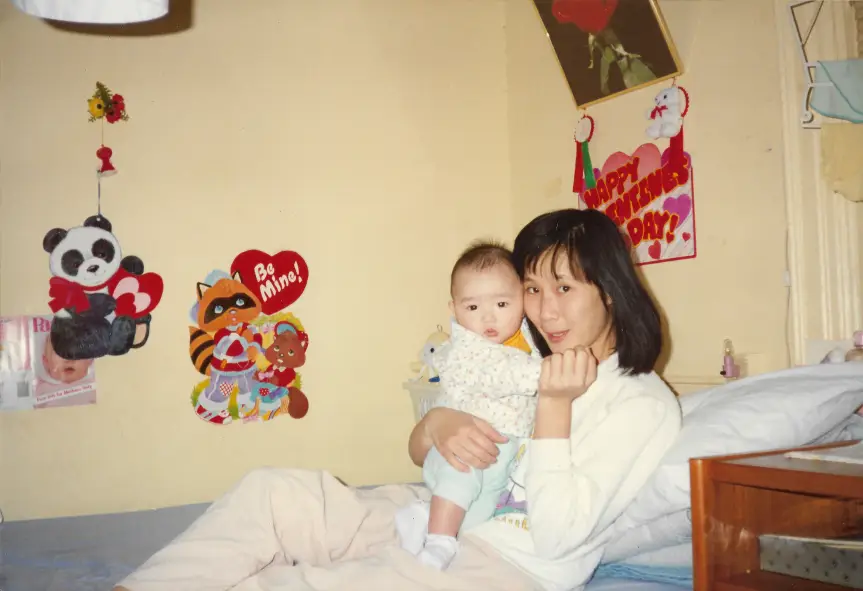

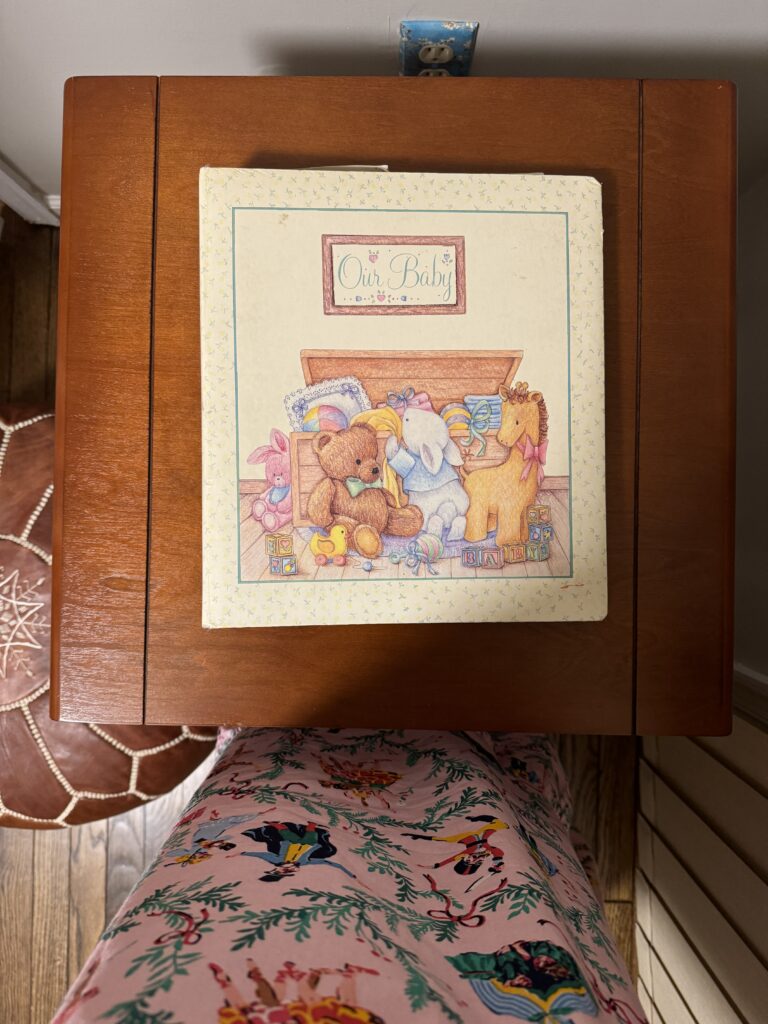

In addition to gaining a daughter, my mother also found a new friend in Cô Hạnh, the doctor who stayed by her side at the hospital whenever she could. Cô Hạnh not only kept her company during those early days but also gifted us our very first baby album–a treasured keepsake we still have today. When it was time to go home, she drove us herself, unwilling to let my mom take the bus. This is the story of my family: one marked by moments of unexpected help and incredible kindness. The generosity of strangers is something my family will always cherish.

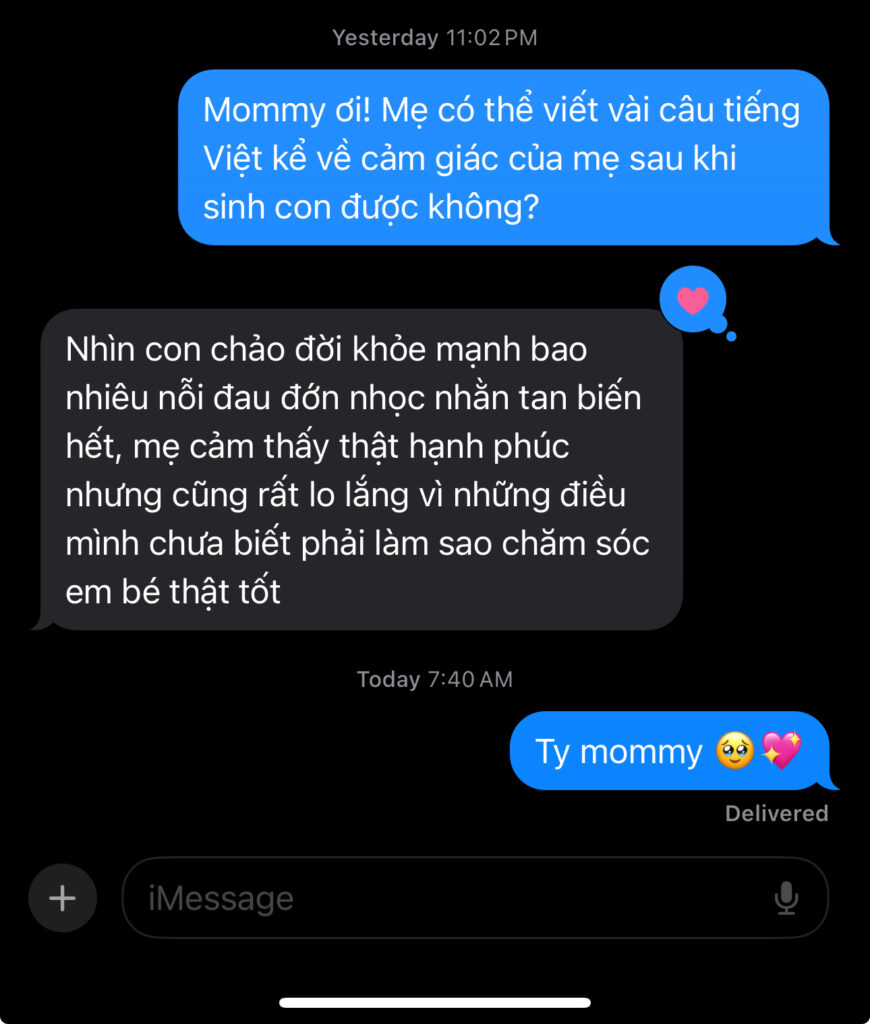

I asked my mom to provide her own words about how she felt after giving birth and she wrote:

Nhìn con chào đời khỏe mạnh bao nhiêu nỗi đau đớn nhọc nhằn tan biến hết. Mẹ cảm thấy thật hạnh phúc nhưng cũng rất lo lắng vì những điều mình chưa biết phải làm sao chăm sóc em bé thật tốt.

You can plug this into Google translate or even chatGPT but it won’t be quite right. Vietnamese is a layered language that relies heavily on context, creative word combinations, and even words not chosen to create new feelings. This is my translation below:

Seeing you greet this world–healthy and vital–how many uncountable moments of suffering and hardship have disintegrated/vanished. I felt elated but also worried, because of the things I knew I had yet to learn to tend to you completely.

To learn more about Vietnam War refugees and how they made their way to the states, check out this wiki page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vietnamese_boat_people

This is so beautiful Kmi!!! 🥹

So beautiful to hear your mom’s story! Thank you for sharing it from her perspective; I felt like I was with them and cheering them on for their first baby girl 🙂